IAM

AWS Identity and Access Management (IAM) is the core authentication and authorization service used across all AWS services. It supports human and machine authentication to AWS APIs, Single Sign-On (SSO) and federated access, and access control to (almost) all resources within AWS.

Critical terms

- Policies - A JSON document that defines a set of permissions that should be granted or denied, potentially based on a set of conditions.

- Roles - The primary IAM entity assigned to resources, can be assumed by users.

- Users - A legacy mechanism for providing human or system access to AWS. To be avoided where at all possible.

- Groups - Collections of IAM users. Can have policies assigned to them, which will then apply to all IAM users in the group.

- Entities - a term used to refer to users, roles or groups as a collective.

Policies

A policy defines what a principal can do within the environment. These are attached to roles, users, or groups to grant or deny permissions. There are three primary categories of policies:

These can then be attached to IAM entities as identity-based policies, or resources (for the services that support it) as resource-based policies.

Policy Types

AWS Managed Policies

AWS defines a number of identity-based policies that you can apply to IAM entities, known as AWS managed policies. These are global across all of AWS, present in every account, and typically scoped for a particular service or with a particular job role in mind. Examples of these include AdministratorAccess, AmazonEC2ReadOnlyAccess, or PowerUserAccess.

These are designed to get users up and running quickly, but should be avoided in production workloads for the following reasons:

- They're always created with

resource: "*", to ensure that they work with whatever naming convention a customer has deployed. - They're broader than will be needed for any specific use case.

- AWS' quality control on them in the past hasn't always been as good as it could be. Some examples:

- https://twitter.com/__steele/status/1316909785607012352

- https://github.com/SummitRoute/csp_security_mistakes#aws-bypasses-in-iam-policies-and-over-privileged

- https://aws.amazon.com/security/security-bulletins/AWS-2021-007/ / https://twitter.com/0xdabbad00/status/1473448889948598275

- https://summitroute.com/blog/2019/06/18/aws_iam_managed_policy_review/

https://github.com/tenchi-security/camp is a useful tool for getting a feel for just how damaging a particular managed policy might be.

Customer Managed Policies

Customer managed policies are policies defined by the account owner within a specific AWS account. They allow users to define a custom set of permissions for a particular IAM entity, and are what most organizations will use to manage permissions held by an entity. They're defined as independent resources within IAM, and a single customer managed policy can be attached to multiple roles, users or groups.

In-Line Policies

In-Line policies are embedded within an entity or resource, and thus can only apply to a single entity at a time.

If writing identity-based policies, customer managed policies are usually a better option than in-line policies. They provide centralized management, policy versioning (so you can roll back if need be), and the ability to delegate out who can assign policies without also needing to grant them rights to alter an entity itself.

Inline policies are generally useful if you want to maintain a strict one-to-one relationship between a policy and the identity to which it is applied. They're also commonly used by AWS solutions like Control Tower and Landing Zone to manage permissions assigned to entities created by those solutions.

Identity-Based Policies

Identity-based policies are policies attached to an IAM role, user or group. These policies define what permissions are explicitly granted or denied to a given IAM entity, to which resources, and under what conditions they apply.

While these can grant permissions to manipulate resources in other accounts, this only applies if the resource itself allows the action too - permissions cannot be unilaterally granted from one account to manipulate resources in another. In practice, this is most commonly seen with granting the ability to assume roles in other accounts, but is sometimes seen to grant data level permissions to resources, such as reading/writing to databases or other data stores.

Resource-Based Policies

Some services support attaching a policy directly to a resource to control access. These are called resource-based policies, and you can use them to restrict conditions under which the resource can be accessed, to grant principals in another AWS account access to the resource and several other things. These are always inline, not managed, and so need to be defined on each resource individually. The list of services supporting resource-based policies is constantly expanding, and the up-to-date list can be found here: AWS services that work with IAM.

Reading a Policy

The below example is taken from the AWS documentation, and grants access to a specific dynamoDB table.

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "ListAndDescribe",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": [

"dynamodb:List*",

"dynamodb:DescribeReservedCapacity*",

"dynamodb:DescribeLimits",

"dynamodb:DescribeTimeToLive"

],

"Resource": "*"

},

{

"Sid": "SpecificTable",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": [

"dynamodb:BatchGet*",

"dynamodb:DescribeStream",

"dynamodb:DescribeTable",

"dynamodb:Get*",

"dynamodb:Query",

"dynamodb:Scan",

"dynamodb:BatchWrite*",

"dynamodb:CreateTable",

"dynamodb:Delete*",

"dynamodb:Update*",

"dynamodb:PutItem"

],

"Resource": "arn:aws:dynamodb:*:*:table/MyTable"

}

]

}

Each policy contains 2 high level blocks:

Version: Almost always 2012-10-17, refers to the policy engine.Statement: A list ofStatementobjects containing the permissions.

Each Statement block contains the following:

Effect:AlloworDenydepending on whether the intent is to grant or block permissions defined in this statement.Action: List of permissions that the policy grants or denies. May include wildcards.Resource: The AWS resources against which the permissions apply, usually defined using their ARNs (Amazon Resource Names). May include wildcards.

A Statement block may also contain the following optional fields:

Sid: Statement ID, a way to name the individual statements.Principal: For resource-based policies, this is to specify which AWS account, role, user, or federated user the policy applies to.Condition: A set of conditions under which the policy applies. May include conditions around date or time of access, originating IP range and several others.

Principal, Action and Resource also have inverses, as NotPrincipal, NotAction and NotResource. These are best used sparingly, as denylist based approaches such as this are inherently less secure. It's also a more common convention to implement a Deny statement with the appropriate fields, than to write an Allow statement with a Not* element.

External Policy References

- Policies and Permissions in IAM

- IAM JSON policy elements reference

- IAM JSON policy elements: Condition operators

- AWS global condition context keys, for a list of all keys that can be used in a

Conditionelement. - Grammar of the IAM JSON policy language

- AWS managed policies for job functions

- permissions.cloud - Permissions Reference for AWS IAM

- Fine-tuning access with AWS IAM Global Condition Keys

Policy Resolution

In IAM policies, things in {} get AND'd and things in [] get OR'd Scott Piper

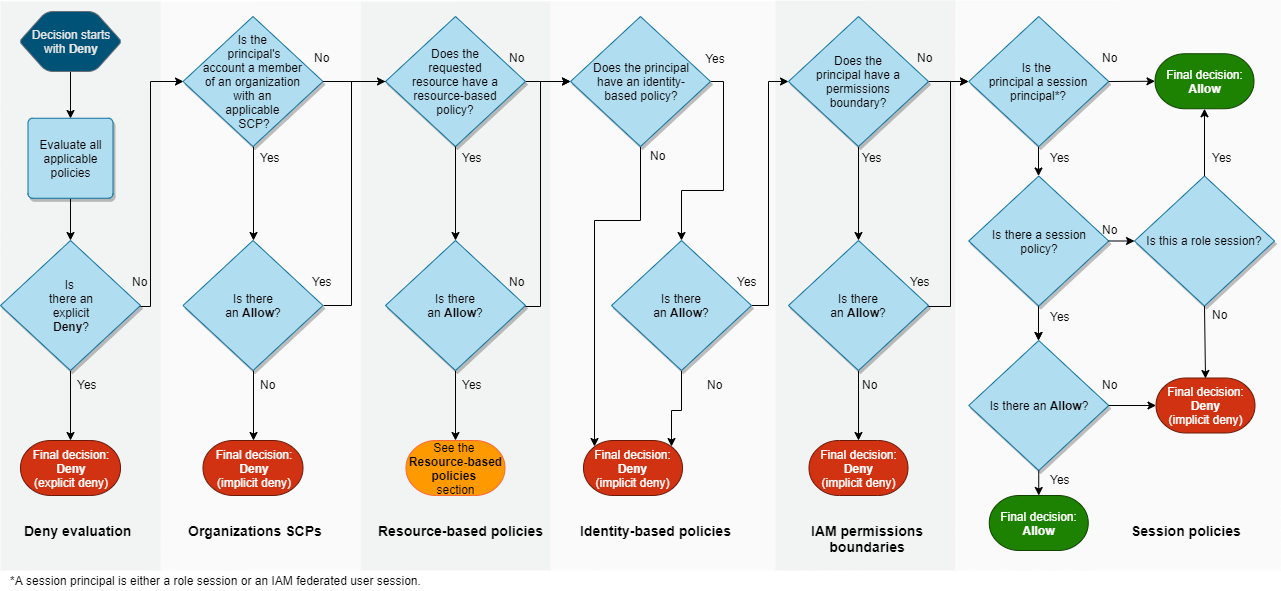

Whenever an AWS principle issues a request, authorisation decision depends on union of all the different policy types that apply. In summary, the process is:

- Default to deny

- Explicit deny always trumps allow

- Only allowed if nothing specifies deny and something allows

The official AWS policy resolution process is documented here, and summarized by the below image:

Permissions boundary

Permissions boundaries are an advanced feature in which you use a (customer or AWS) managed policy to limit the maximum permissions that an entity can have. They act as an explicit deny, and can thus be used to prevent actions that might otherwise be allowed by identity-based policies.

You cannot apply a permissions boundary to a service-linked role.

Session Policies

Session policies are policies passed as a parameter when a temporary session is created for a role (or federated user). They provide a means to deny permissions that are defined in a role's identity based policies for a specific session, rather than for the role in general as a permissions boundary would.

Roles

A role is an IAM entity that can be "assumed" by AWS resources, or by an external system or human user through federated access. AWS issues short-term, temporary credentials associated with a role when something assumes it, with a maximum duration of 12 hours. Roles can be assumed by the following:

- A service offered by AWS, such as Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (Amazon EC2), Lambda or others.

- An external user authenticated by an external identity provider (IdP) service that is compatible with SAML 2.0 or OpenID Connect, or a custom-built identity broker.

Roles should be used for everything where at all possible, both human access and system authentication

Role Assumption

Roles can be assumed by entities within the account, or from a different account. In order for a role to be assumed:

- The assuming entity must have the

sts:AssumeRolepermission granted to allow them to assume the chosen role. - The trust policy on the role being assumed must allow assumption by the assuming entity.

n.b Not all tools take both these conditions into account, you’ll find some report false positives where they only analyse the trust policies.

Trust Policies

Also known as an AssumeRolePolicyDocument, these are special versions of a policy in which you define who is allowed to assume the role. sts:AssumeRole is the only valid permission in a trust policy. This trusted entity is included in the policy as the principal element in the document, and conditions can be set as to how and where the role can be assumed from. An example of a simple trust policy, in this case granting permission to EMR and DataPipeline to assume the role, is included below.

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": {

"Service": [

"elasticmapreduce.amazonaws.com",

"datapipeline.amazonaws.com"

]

},

"Action": "sts:AssumeRole"

}

]

}

The trust policy below grants permission for users and roles in the 123456789012 account to assume the role, under the condition that the traffic originates from 123.45.167.89.

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": {

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": {

"AWS": "arn:aws:iam::123456789012:root"

},

"Action": "sts:AssumeRole",

"Condition": {

"IpAddress": {"aws:SourceIp": "123.45.167.89"}

}

}

}

}

n.b the root ARN for an account when used in a trust policy, arn:aws:iam::123456789012:root above, does not refer to the root user. It grants access to all IAM roles, users and groups in that account, essentially stating that the role trusts that any appropriate access controls are enforced within the other account.

A more in-depth guide to trust policies can be found in the AWS documentation..

Condition keys in policies can be useful for preventing temporary access keys from being used outside of the environment in which they were issued, using Source VPC IDs and Session Policies.

The Confused Deputy Problem and External IDs

Cross-account access via role assumption from third party vendors is a common pattern in AWS, where this access mechanism is used by things like centralized logging, cloud security posture management (CSPM) platforms, third party CI/CD tools and so on. This is subject to the confused deputy problem, where a legitimate system is tricked by a malicious entity into misusing its authority. In the context of AWS, an attacker might sign themselves up to a third party SaaS platform that the victim is known to use, then configure their account on the platform to use the victim's AWS account ID and role names. The platform has access to the victim's AWS account, as the victim has granted that access, and so the attacker can trick the platform into taking actions against the victim's AWS account on the attacker's behalf.

AWS' solution to this is External IDs, where the third party provides a unique identifier that can be included in a role trust policy. This value does not need to be kept secret, but it is important that the third party vendor generates this, and that it cannot be configured by the customer. The example below, taken from AWS' External ID documentation illustrates how this is used in practice.

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": {

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": {"AWS": "Example Corp's AWS Account ID"},

"Action": "sts:AssumeRole",

"Condition": {"StringEquals": {"sts:ExternalId": "12345"}}

}

}

It's common to see vendors fail to implement ExternalId correctly, so worth checking for when looking at third party access into an AWS estate.

Instance Profile

Instance profiles are a wrapper around IAM roles used to assign an IAM role to a particular EC2 instance. Software running on the instance can then access the associated credentials by speaking with the Instance Metadata Service (IMDS).

Service-Linked Roles

Some services in AWS support Service linked roles. These are roles that are linked directly to an AWS service. Service-linked roles are predefined by the service and include all the permissions that the service requires to call other AWS services on your behalf.

The linked service also defines how you create, modify, and delete a service-linked role. A service might automatically create or delete the role with no customization possible, or it may allow you to define or modify it yourself.

AWS Services That Work with IAM defines which services use Service-Linked Roles.

Role chaining

Role chaining occurs when you use a role to assume a second role through the AWS CLI or API. For example, assume that IAM User User1 has permission to assume RoleA. Additionally, RoleA has permission to assume RoleB. RoleA can be assumed using User1's long-term user credentials in the AssumeRole API operation. This operation returns RoleA's short-term credentials. RoleA's short-term credentials can then be used to assume RoleB.

Role chaining limits your AWS CLI or API role session to a maximum of one hour. When you use the sts:AssumeRole API operation to assume a role, you can specify the duration of your role session with the DurationSeconds parameter. You can specify a parameter value of up to 43200 seconds (12 hours), depending on the maximum session duration setting for your role. However, if you assume a role using role chaining and provide a DurationSeconds parameter value greater than one hour, the operation fails. Whenever a role is assumed, the expiry time for the associated credentials is set based on the time of assumption, not based on the validity of credentials doing the assuming. As such, in the example above, it's possible to generate credentials for RoleB valid for an hour using credentials for RoleA that are due to expire shortly.

In practice, it's common to see role chaining happening with human users through SSO. An initial read-only role may be assumed through the SSO, and then a privileged role assumed from there (much as with sudo on Linux systems).

Role Juggling

A corollary of role chaining is that if you find roles whose trust policies allow them to assume themselves, or sets of roles that can assume each other in a circular trust relationship, it's possible to persist long-term by repeating the role assumption round the chain over and over. This technique is known as Role Juggling - AWSRoleJuggler is a tool that helps to identify and exploit this issue.

Federation

Federation allows customers to use an external identity provider (IdP) to authenticate their users to AWS. Users can sign in to a web identity provider that is compatible with OpenID Connect (OIDC), such as Google or Github, or with Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML) 2.0, such as Microsoft Active Directory Federation Services (ADFS).

Once authenticated through an external IdP, AWS then presents a user with roles they are allowed to assume if authenticated through the browser. If done through the CLI or other tools, the role name is usually supplied there. The user then receives temporary credentials with permissions associated with the role, issued by STS (AWS Security Token Service).

In practice, there is no consistent recommended approach for implementing federated access across AWS, so there's a wide range of approaches, custom tools, etc across different organizations. AWS SSO, backed by an external IdP, is the officially recommended route now due to native support in the AWS CLI. Common options taken include:

- ADFS integrated with on-premises Active Directory.

- Azure Active Directory.

- Third party dedicated SSO providers like Okta, Auth0, OneLogin etc.

It's common to see organizations using custom scripts or open source tools to grant CLI and API access through federation. Most SSO providers offer their own, but it's also common to see these used:

PassRole permission

The iam:passrole permission is used to allow principals to pass roles to various services. It can also be abused for privilege escalation if it is not appropriately restricted (you can pass the admin role to an EC2 instance which you have access to). A detailed list of all the actions that require the iam:passrole permission can be found here: https://gist.github.com/noamsdahan/928aafbcca71f95b07472f22e35dc93c

IAM Users

IAM Users are a legacy mechanism to provide authentication to human users (and sometimes systems outside of AWS). They're created locally within a specific AWS account, and can have two types of credentials:

- Username/password - Used to authenticate to the web console.

- Access Keys - Used to authenticate to the APIs, with the CLI or any other tool.

These should be considered the root of most evil in AWS security, and should be purged with fire at every opportunity.

Root User

The root user is a special case of IAM user that exists in every AWS account, cannot be disabled or removed, and has a permission set equivalent to *:* . General recommendation is to avoid ever using this account where possible, and definitely don't generate access keys for it. Many organizations throw away the AWS-generated password when creating an account tied to an Organization, as the password can be recovered via AWS Support if need be. If the password is kept, this account should have strong MFA (multi-factor authentication) enforced on it, and the MFA tokens and password should be treated as extremely sensitive. The only way to restrict the permissions of a root user is with SCPs (Service Control Policies), if the account exists within an organization.

The root user is required for a small number of operations, at time of writing this was limited to:

- Change some account settings, including the account name, email address, root user password, and root user access keys.

- Activate IAM access to the Billing and Cost Management console.

- View certain tax invoices.

- Close your AWS account.

- Change or cancel your AWS Support plan.

- Register as a seller in the Reserved Instance Marketplace.

- Configure an Amazon S3 bucket to enable MFA (multi-factor authentication).

- Edit or delete an Amazon Simple Storage Service (Amazon S3) bucket policy that includes an invalid virtual private cloud (VPC) ID or VPC endpoint ID.

- Sign up for GovCloud.

Access Keys

Access keys are the credentials used to authenticate requests to the AWS APIs, and are typically used in combination with the AWS CLI or one of the language-specific SDKs.

- Access Key ID - Roughly equivalent to a username, this is the (theoretically) unique identifier for the set of access keys you’re using. This can be found in CloudTrail logs when using long-lived access keys. The first few characters can be used to identify what the key is associated with.

- Secret Access Key - The secret component of any set of credentials, these are used to sign requests to the AWS API. Consider them equivalent to a password, and protect them accordingly.

- Session Token - Only required with temporary keys, these are passed alongside the Secret Access Key in the

X-Amz-Security-Tokenheader or query string field. These serve as a secondary identifier, the suspicion is that key IDs for temporary tokens are not globally unique

A summary of the core concepts is included below, for a more complete explanation and reference, look to https://www.nojones.net/posts/aws-access-keys-a-reference/

User Access Keys

These are long lived access keys tied to an IAM user. They do not expire, and so are valid until deleted. If an organization doesn't have an SSO in place, they're sometimes used by human users. They're also commonly used to allow systems hosted elsewhere to authenticate to AWS.

Avoid wherever possible - This cannot be overstated. The unlimited validity means that, if they're stolen, an attacker will maintain access until the keys are manually deleted or rotated. Leaked user access keys (often inadvertently published to public GitHub repositories) are a consistent source of breaches in AWS. There are very few legitimate use cases for these now, and alternative options should always be explored. Some options:

- For users:

- AWS SSO.

- Federated access through an external identity provider such as Active Directory, Ping, Auth0, OneLogin.

- For systems:

- AWS IAM roles assigned to the compute resources.

- OpenID Connect, with external services that support it. GitHub Actions is a good example here, where Actions can assume a role in an AWS account using an OIDC token issued by GitHub.

Gaining Console Access from Access Keys

sts:GetFederationToken can be used to get a valid web console token from IAM user keys. https://github.com/NetSPI/aws_consoler will automate that. Expect this to often be blocked by IAM permissions, as sts:GetFederationToken is not commonly used.

Temporary Keys

These are temporary keys issued by AWS STS. They're generated on the fly by STS when a user or system calls sts:AssumeRole or similar. These are the recommended means to authenticate users and systems to AWS, because the credentials are short-lived. They're usually only valid for a maximum of 12 hours (though frequently much less). These are the keys issued to users who authenticate through a single sign-on platform.

For AWS services with roles assigned, they're generated and issued transparently by the underlying AWS platform, and provisioned through either the relevant instance metadata service or environment variables. The locations of the different metadata services are outlined in Hunting for Access Keys below.

API calls that return credentials

Kinnaird McQuade maintains a list of AWS API calls that generate and return credentials here: https://gist.github.com/kmcquade/33860a617e651104d243c324ddf7992a

Service Control Policy (SCP)

A feature of AWS Organizations that supports blocking actions across entire accounts or OUs in the organization. They operate in a similar manner to permission boundaries with regards to limiting the maximum permissions a role may have. They can block even the root user in an account from taking particular actions.

See the Organization page for more detail, but in summary, SCPs:

- Control maximum available permissions for all accounts in the organization.

- Block even the root user from performing actions.

- Applied to OUs, cascades down through sub-OUs.

- Where multiple SCPs apply, restrictions are cumulative.

- Expect to have these block a lot of your actions on an engagement.

Assessment notes

Offensive

External Enumeration

- You can enumerate roles deployed in an AWS account by analysing the error messages.

- It's also possible to enumerate roles by attempting to configure them in a role's trust policy.

Hunting for Access Keys

Common locations include:

- Environment variables

- Access keys can be passed in as environment variables to a given environment. They are always stored in the following environment variables:

AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID- Access key ID.AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY- Secret access key.AWS_SESSION_TOKEN- Session token.

- Lambda uses environment variables to provision access keys to a function too.

- Access keys can be passed in as environment variables to a given environment. They are always stored in the following environment variables:

- On-disk configuration files

~/.aws/credentials— Intended as the proper location to store access keys.~/.aws/config— Configuration for each profile, but may also hold credentials.- https://ben11kehoe.medium.com/aws-configuration-files-explained-9a7ea7a5b42e for a deeper explanation of these files.

- EC2-style instance metadata service (IMDS)

- v1: unauthenticated web requests

- http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/ will list the roles provisioned on the instance.

- http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/ROLE-NAME will return the access keys associated with the ROLE-NAME role.

- v2: requires token for sensitive API calls, to defend against SSRF attacks

- Request a token by submitting a PUT request to http://169.254.169.254/latest/api/token.

- Pass the token in the X-aws-ec2-metadata-token header for other requests.

TOKEN=`curl -X PUT "http://169.254.169.254/latest/api/token"` && curl http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/ROLE-NAME -H "X-aws-ec2-metadata-token: $TOKEN"

- https://hackingthe.cloud/aws/general-knowledge/intro_metadata_service/ for more details, including differences between v1 and v2.

- v1: unauthenticated web requests

- ECS-style instance metadata service (IMDS)

169.254.170.2$AWS_CONTAINER_CREDENTIALS_RELATIVE_URI- Also used by:

- Sagemaker Notebooks

- App Runner

- CodeBuild

- Batch

- CloudShell-style instance metadata service (IMDS)

$AWS_CONTAINER_CREDENTIALS_FULL_URIwith$AWS_CONTAINER_AUTHORIZATION_TOKENsent in theAuthorizationheader.

Outside AWS

It's common to find access keys scattered around in code repositories, home directories, and all kinds of other places. Start by exploring:

- Confluence, SharePoint, other wikis, documentation sites and knowledge bases

- Git repositories - Several good tools for this, including:

- User home directories and their backups, especially in

~/.aws/.

Some good search queries to use include:

AKIAaws_access_key_idaws_secret_access_keyAccessKeyIDSecretAccessKey

Once you have keys

Whoami

aws sts get-caller-identitywill return the account and ARN for the IAM entity the keys are associated with. This call is not commonly used in all environments, so there's a reasonable chance it'll stand out in CloudTrail logs, but the API call requires no permissions and will always work if the keys are valid.

IAM Enumeration

Expect much of this to fail, as many roles and users will not have the necessary permissions:

aws iam get-account-authorization-details- Get the account's entire IAM configuration in one big JSON file. Very infrequently used, so will stand out.aws iam get-role --role-name [take from arn in get-caller-identity]- Get details of a role.aws iam get-policy / get-policy-version- Get policy metadata, submit default policy version number toget-policy-versionto get the policy contents.aws iam get-role-policy- Download inline policy documents associated with a role.aws iam list-attached-role-policies- List managed policies associated with a role.

Privilege Escalation

Privilege escalation in AWS mostly relies on exploitation of misconfigured permissions granted to a lower-privileged role that an attacker has access to. It's common to have to work these out either blind or semi-blind, as evaluating whether something is possible is challeging and requires a lot of information thanks to the complexity of the policy resolution logic AWS has implemented. It's often not possible to enumerate parts of the permissions model in offensive situations, as SCPs, resource-based policies, etc are often not readable from an initial foothold.

Defensive

Data Gathering

aws iam get-account-authorization-detailsgives you the contents of the account's IAM configuraiton in one single JSON file. Generally easier to work with than making lots of individual API calls.

Assessing Policies

Business and operational context will be needed to catch anything more than the most obvious mistakes here.

Mapping/visualisation tools will help you to understand how the different policies apply within an account.

The usual principle of least privilege applies - look for cases where wildcards are being used, where excessive permissions are granted and so on.

Points of major concern include:

- Particularly dangerous managed policies:

AdministratorAccessIAMFullAccess

- Any use of the

"*"permission. - Any use of any

iam:permissions that allow modification. - Unlimited IAM write/modify is effectively full administrator access, so pay particular attention to

iam:actions. - Any policies that contain permissions discussed in the privilege escalation section.

- Particularly dangerous managed policies:

Whether they enforce MFA on their human IAM users

- If they're using federated access, MFA needs to be enforced on the identity provider, not AWS.

- IAM Users used by external systems (on-premises Jenkins etc) should not be expected to use MFA.

- To implement that,

aws:MultiFactorAuthPresentboolean condition must be added to either the in-line policy or an attached policy on a given user or group in order to enforce MFA. This is usually done as adenypolicy configured to block everything unless that condition is true, but can also be used to require MFA for higher privileged actions by configuring a deny policy that applies only to privileged actions.

Whether they've implemented IP allowlisting to restrict where people can access the console and API from

IP allowlisting requires a

not IP addressfilter attached to adenypolicy:"Condition": {

"NotIpAddress": {

"aws:SourceIp": [

"192.0.2.0/24",

"203.0.113.0/24"

]

}

}

Dangerous Permissions

Ian McKay published a list of expensive and long-term effect IAM actions, it's worth scrutinizing anything with these permissions particularly carefully.

Access Advisor

Access Advisor is an AWS tool that indicates what services an IAM entity has been accessing, and what permissions the entity has been making use of. This is useful to identify what access an entity really requires, and then compare that against what they've been configured with.

Access Advisor Web Console

To access in the web console: iam -> users -> select user -> access advisor

Access Advisor CLI/API

Details of the Access Advisor CLI/API can be found at https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/security/automate-analyzing-permissions-using-iam-access-advisor.

Access Analyzer

IAM Access Analyzer analyses the resources in an account to identify those that can be accessed by an external user from an external account. The external users can be an AWS account, root user, IAM user, IAM role, federated user, AWS service, the anonymous user, or any other entities.

More detail on Access Analyzer can be found on the AWS site. It can also be used across AWS Organizations as a whole

IAM Credentials Report

The IAM credential report lists all IAM Users and the states of all their credentials - API keys, passwords, MFA, etc. This is useful for:

- Finding unused API keys.

- Finding API keys that are overdue for rotation.

- Finding cases where IAM users used by systems have console access configured.

Permissions Required

GenerateCredentialReportto create.GetCredentialReportto download.

AWS CLI commands to generate and download

aws iam generate-credential-reportaws iam get-credential-report

Common Tooling

- https://github.com/WithSecureLabs/iamspy - An SMT solver that mimics the AWS IAM policy resolution engine, and will answer questions on who can do what in an AWS account.

- https://github.com/nccgroup/PMapper - Graph-based IAM permissions analysis for individual accounts or Organizations.

- https://github.com/duo-labs/parliament - IAM linting library in python, looks for policy errors and bad practices.

- https://github.com/salesforce/cloudsplaining - Identifies data exfiltration, infrastructure modification, resource exposure, and privilege escalation issues with policies in an account.

- https://github.com/salesforce/policy_sentry - Least privilege policy generator.

- https://github.com/duo-labs/cloudmapper - Security auditing with IAM support included.

- https://github.com/RhinoSecurityLabs/pacu - AWS exploitation framework.

- https://github.com/lyft/cartography - Cloud infrastructure relationship mapping, with good support for IAM.

- https://github.com/prisma-cloud/IAMFinder - External enumeration of IAM users and roles.

- https://github.com/WithSecureLabs/awspx - A graph-based tool for visualizing effective access and resource relationships in an AWS account. Unmaintained, but still sometimes useful.

External References

- Rhino Security's privilege escalation guides

- Bishop Fox's privilege escalation guides, building on Rhino's work

- The hackingthe.cloud guide on IAM privilege escalation

- Scott Piper's guide on assessing and auditing IAM policies